Biophysical solutions

Some solutions to desertification are given here. However, as indicated by the complexity of the desertification problem, a single solution will not solve it. Moreover, there should be the recognition that prevention is the most cost-effective solution to degradation.

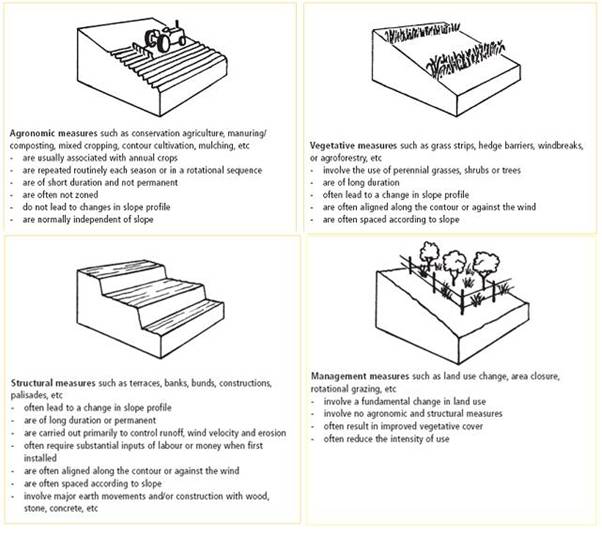

Biophysical solutions can be categorised into a few major groupings (WOCAT, 2007), see Figure 7.1

Figure 7.1: categories of Soil and Water Conservation (SWC) measures

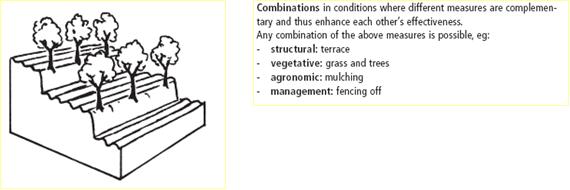

A solution (or practice) may fall within one of the above categories, but very commonly also consists of a combination of these. These combined measures - overlapping, or spaced over a catchment/ landscape, or over time - tend to be the most versatile and the most effective in difficult situations: they are worthy of more emphasis (WOCAT, 2007).

Below follow a number of bio-physical solutions that address one or several specific degradation problems.

Water conservation/harvesting

In dry areas the availability of water is of prime importance. One of the basic principles to achieve this is conservation and/or harvesting of surface and groundwater and soil moisture. Irrigation techniques should be optimised, e.g. drip irrigation is more water efficient than sprinkler or flow irrigation (Portnov and Safriel, 2004). Techniques like mulching and minimum tillage reduce evaporation losses. Terraces and cross-slope barriers like hedges, trash or stone lines reduce the speed of the water flow and thereby enhance infiltration. Water can also be actively harvested from rainfall or streams by diverting it to above or underground storage reservoirs or more simply in the field by creating mini catchment basins such as the "half-moon" technique practiced in N. Africa.

Technical solutions to the water problem in Spain include the building of many reservoirs, the transfer of water and desalinization of seawater (Conacher and Sala, 1998). Especially the second gives rise to much debate and should be used with caution as it changes the waterbalance in both receiving and supplying watersheds and can have unforeseen results. The avoidance of leakages in water distribution networks and an increase of the awareness that water is scarce to the population could also help in increasing water use efficiency (Conacher and Sala, 1998). Stabilizing channel walls with sometimes massive techniques in France is not considered a durable solution as undermining by the current will eventually lead to the collapse of the structure.

In the eastern Mediterranean, waste-water is being treated and re-used for irrigation or to replenish the coastal aquifer (Conacher and Sala, 1998).

Erosion reduction

The majority of measures to control land degradation is aimed at reducing or preventing erosion. Erosion control can be achieved essentially in two ways: reducing the sensitivity of the soil to eroding agents (erodibility; e.g. increase the soil organic matter content, reduce or break up the slope, cross-slope barriers) and reducing the impact of rainfall erosivity e.g. by increasing vegetation cover (Stroosnijder, 2000). Structural measures against various forms of erosion are widespread (terraces, gully plugs, check dams, etc.) but are not always the most (cost-)effective. While generally successfully reducing run-off and sediment transport, the erosion problem itself is not always solved: e.g. while upstream erosion is reduced, it is increased downstream due to the higher erosive power of the clear water (Hook and Mant, 2000; Conacher and Sala, 1998). Moreover, terraces may stop erosion but not necessarily increase yields and income. A live or dead vegetative cover in vineyards , e.g. with grasses or mulch, is a very efficient and (more) cost-effective means of preventing soil erosion. Reforestation is another popular but increasingly challenged solution. Plantations of Aleppo pines and eucalyptus trees were established in Italy, notably in the 1960s and 70s to reduce erosion. They have proved to be of limited benefit, as following an initial phase of reduced soil loss, a resurgence of erosion normally occurs and severe piping develops (Sorriso-Valve et al., 1992, 1995).

In northern Africa, a widely used conservation technique is stone bunds built with large stones and rocks that are removed from the field. The bund reduces the speed of run-off water and allow the natural creation of small terraces. They also hinder the entrance of livestock on the fields thereby reducing the damage of (over)grazing and browsing.(Conacher and Sala, 1998).

Conservation agriculture is increasingly being applied, e.g. in southern Spain (Conacher and Sala, 1998). It is not a single measure but a broad concept which includes minimum tillage, crop rotation, optimum soil cover, direct seeding and the correct use of herbicides, the need for which is increased by the reduction of ploughing. In Greece, soil erosion is being controlled by a system composed of conservation tillage, contour farming, terracing, grassed waterways and maintaining a rich vegetation cover (Conacher and Sala, 1998).

Grazing management

The issue of overgrazing is often related to the political desire of settlement of nomadic people. However, herds in dryland areas should be allowed to follow the rains. If this is neglected, year-round grazing at one specific location may lead to overgrazing. Enclosing pastures, i.e. part of the grazing land is closed to grazing livestock to allow the pasture to recover naturally, may work for that particular piece of land, but it increases pressure on other parts, possibly exacerbating the problem (Fan and Zhou, 2001). Planting of improved grass and (other) fodder species either or not in combination with stall feeding may also provide a solution.

Salinization

Salinization is another common problem in dryland areas, especially under irrigation. This can occur when land is irrigated and no appropriate drainage system is in place. With the capillary rise of the water salts are transported to the surface and remain there after the water evaporates. Proper drainage or other measures to lower the water table (e.g. planting poplars in Kyrgyzstan, WOCAT, 2007) is a possible solution while the irrigation water should also be of good quality.

Wildfire control

Land degradation by wildfires can be tackled in two main ways: fire hazard reduction and post-fire remediation. In the former, fuel load reduction methods and forest and land management practice changes are aimed at limiting the spread and degree of destruction by wildfire. The fuel load can be reduced by means of understorey clearance, herbicides, grazing and ploughing at the individual tree, tree stand and forest scales. Improved choice of tree species to match the climatic and topographic characteristics to reduce the impact of wildfire has also been proposed. These measures have been discussed with respect to Portugal (see chapters in Silva 2002). An alternative approach is prescribed fire, which involves burning the understorey and litter under controlled conditions to reduce the destructive effect of any subsequent wildfire. Following realisation of the disastrous effects of fuel load build-up resulting from attempting to suppress all fires, it has been become an accepted tool in North America during the late 20th century (e.g. Neary et al. 1999) and Australia (e.g. Morrison et al. 1996), but it has been only relatively recently been considered in Portugal (Fernandes and Botelho 2003).

As regards post-fire remediation, measures can be divided into three categories: emergency stabilization, rehabilitation and restoration. Emergency measures include mulching to prevent soil erosion, the introduction of barriers (e.g. log barriers) at strategic points in the burnt landscape to intercept particularly erosive overland flow and reduce soil erosion (e.g. Marqués and Mora 1998; Fox et al. 2006) and the planting of grass 'filter' strips (Robichaud 2005). Rehabilitation encompasses activities undertaken over several years to repair roads, bridges etc. and plant trees and reduce fuel loads. Restoration refers to longer-term measures aimed at improving the resilience and maturity of the ecosystem (e.g. Vallejo and Alloza 1998; Silva 2002b; Espelta et al. 2003). For the DESIRE project, it is intended to assess the effectiveness of some of these measures about which little is known in the Mediterranean context, especially prescribed fire and emergency post-fire mitigation measures.