Major natural resources available

Geology

Throughout the geologic history of Crete the following deposits and tectonic units appeared in a more or less successive, overlapping sequence: the Crete-Mani geo-tectonic unit (semi-metamorphic platy-limestones), the Crystalline carbonate unit of Trypalion, the Phylite-Quartzitic basement and its carbonate alpine cover of Tripolitza-geotectonic zone and the overlapping nappes of Pindus and of the more internal Hellenides geotectonic zones. All pre-alpine formations are intensively folded, thrusted and faulted. The morphologic lower parts and basins of the island are covered by thick clastic sediment of Neogene and Quaternary. Since Minoan times and as far as the geological frame is concerned, the only probable changes could not have gone beyond slightly erosional modifications in the physiography, the groundwater table level and the recent geological formations (Angelakis and Spyridakis, 1996a).

Soils and terrain

The soils of Crete formed on the above geological formations are typical of the Mediterranean region and they were mainly affected by topography and management practices. Deep alluvial soils of various textures, rich in carbonates were formed in the bottomlands (Fluvisols, and Gleysols). Deep soils of various textures free of carbonates with a cambic or an argillic horizon and various degrees of erosion were formed on alluvial terraces of Quaternary age (Luvisols, Cambisols, and Regosols). The soils formed in hilly areas are characterized by their advanced degree of erosion with the parent material exposed on the soil surfaces in several cases (Cambisols and Leptosols).

The Chania region is characterized by a variety of landscapes, and lithological units. Soils are formed on a variety of parent materials such as limestone, shale, marl, conglomerates and alluvial deposits. Slope gradient ranges from almost flat (slope ~ <2%) to very steep (slope ~ >35%) with dominant classes greater than 18%. Soil depth ranges from shallow (depth <30 cm) to very deep (depth >150 cm). Soils formed on marl, conglomerates, and alluvial deposits are relatively deep (soil depth >75 cm), while soils formed on shale and limestone are shallow to moderately deep (depth 15-120 cm).

As the Chania region, Messara valley is characterized by a variety of landscapes and lithological characteristics. The plain part of the valley consists of alluvial Pleistocene-Neogene deposits, while the bordering sloping part of the valley consists of mainly of marly or clayey deposits and by flysch and limestone parent materials. The soils can be classified into three broad categories: (a) recent alluvial soils which do not show any profile development located in the bottom of the valley classified as Fluvisols and Gleysols, (b) soils of the older Pleistocene terraces which show distinct horizon differentiation classified as Luvisols, and (c) eroded soils of hills classified as Cambisols or Regosols. Slope gradient ranges from almost flat (slope <2%) to very steep (slope >35%) with dominant classes greater than 12%. Soil depth ranges from shallow (depth <30 cm) to very deep (depth >150 cm).

Climate

The climate of Crete is dry sub-humid Mediterranean with humid and relatively cold winters and dry and warm summers. The annual rainfall ranges from 400 mm to 700 mm in the low areas and along the coast (lerapetra 412 mm, Iraklio 512 mm, Chania 665 mm), and from 700 to 1000 mm in the plains of the mainland, while in the mountainous areas reaches up to 2000 mm. Such great climatologically differences are due to the complex vertical and horizontal distribution of Crete. During winter, which starts in November, the weather is unstable due to frequent changes from low to high pressures. Rainfall has decreased in the island in the last decades for more about 30%, however, long series rainfall data in all over Crete does not show any significant change in precipitation (Markou-lakovaki, 1979; Macheras and Koliva-Machera, 1990).

Despite considerable high precipitation (600 m in the plains and 2000 mm in the mountains), water consumption and use constitutes a relatively small portion due to unequal temporal and regional distribution and high evapotranspiration rates. About 45 % of total precipitation occurs in the months of December and January. From the total plains' precipitation per year, it is estimated that about 65 % is lost to evapotranspiration, 10 % as runoff to sea and only 25 % goes to recharging the groundwater.

Spring is short because of the cold fronts often affecting the region in March, whereas May is rather warm especially due to the appearance of the first south winds and the disappearance of the action of low pressures. North winds are dominant in the island. In summer winds create very dry conditions, which are also enhanced by the diminishing of low pressures in eastern Mediterranean and are only interrupted by some local rainfalls of tropical origin. Heat waves in the plains during summer may be rather lasting, affected by south winds blowing from Africa.

Concerning air temperature Crete shows a great variation. It lies between the isotherms 18.5°C to 19.0°C with an annual amplitude of 14°C to 15°C. The southern part of the island is warmer than the northern part and the warmest of Greece. During the cold period, temperature increases with decreasing latitude, whereas in the warm period and especially in the period from May to August, temperature increases from the coast to the mainland and particularly in the plains. In winter, the lowest temperatures scarcely fall below 0°C in the plains. During the summer, temperatures greater than 40°C may occur in the lowlands of Crete. The annual temperature has increased in the last two decades by 0.3°C.

The Chania region has an average annual rainfall of 627 mm in the lowland increasing by about 30% in the upper mountainous areas. Based on the last 40 years data, rainfall has decreased in an average estimated to 24.5%. The average air temperature is 18.7°C decreasing in the upper region by about 2 degrees. The warmer month is July with an average temperature 28.3°C, while the coldest month is January with an average temperature 10.2°C. A high temperature above 40°C occurs sometimes during summer for few days per month causing problems in the growing plants accompanied by increasing water demands for irrigation. Very low temperature (bellow 0) rarely occurs especially in the lower zone of study area during the winter period. The incidence of frost is not often since minimum temperature hardly drops to levels that affect olive trees, citrus and vegetables.

The Messara valley has an annual rainfall of 570 mm in the lowland, increasing by about 35% in the upper hilly areas close to Psyloriti mountain. Precipitation has significantly decreased in the last twenty years in the Messara valley. A reduction of about 44 % in rainfall has occurred in the last three decades. The average air temperature is 19°C decreasing in the upper region by about 2 degrees. The warmest month is July with an average temperature of 28.4°C, while the coldest month is January with an average temperature 11.0°C. As in the area of Chania, extreme air temperature above 40°C occurs for some days during summer period. Very low temperatures (below 0°C) rarely occur during the winter months.

Vegetation

The historical evolution of the natural vegetation of Crete followed the turbulent history of the island (Bambakopoulou, 1985). After the degradation of the Minoan civilization (1400 B.C.), the Myceneans invaded the island. The Cretans either because they were expelled or due to aversion to the invaders, they moved up to the mountains and created communities inside the forests, after clearing first large areas for cultivation and animal breeding. Later, in the period 327-287 B.C., in his book "About the history of plants", Theophrastus, the father of the Botanical science, refers to the great spreading of cypress forest in the area.

During the Roman occupation that followed (1 B.C. - 9 A.D.), Gaius Plinius Secundus, Ploutarchos, Hysichos, and other travelers that visited the island and observed, admired and described the natural forests and annual vegetation. Gaius Plinius Secundus (23-79 A.D.) in his book "Natural History", states that cypress were so plenty growing on the mountain Idi, that someone may got the impression that the region was the land of cypress. Ploutarchos (46-127 A.D.) speaks about forests of cypress, and states that in the area was rich in timber for ship-construction. In his Dictionary, Hysichos ( 5th century A.D.) states that the name of the mountain Idi or Ida comes from the very dense forests completely covering the mountain in ancient times, where many springs and streams existed. After the invasion of Venetians in the 13th century, a great colonization of the uplands and mountains took place. During the occupation by the Venetians, many forests were cleared to produce timber for exports, especially timber from cypress or ship-building. Apparently timbering was not the most important cause of destruction, considering that (up to a certain point) the forest could regenerate itself.

The Venetians occupation finished with the Turkish invasion in the 17th century. During the period until 1775, the Turkish occupation was not too harsh, until the eruption of the "Daskalogiannis revolution" that brought about a tougher occupation and revenges by the Greeks.

During Turkish occupation the rebels put the forests in fire in order to harm the Turkish economy, but on the other side, the Turks were burning the forests on the mountains to distract the rebel communities. Due to the tough occupation and the pressure that they suffered, more and more people migrated to the uplands and mountains creating new mountainous communities. Such great migration of the population to the hilly and mountainous regions during the Venetians and Turkish occupations affected negatively the natural vegetation of the populated upland and mountainous areas. The creation of new communities and the need for more and more arable and grazing land led to further degradation of the forests (Bambakopoulou, 1985).

After the revolution against Turkish occupation (ca. 1900 A.D.), the shepherds, who until that time remained on the high mountains, started moving off the hills to the lowland in order to pass the winter. In the mean time they set fires in the densely vegetated areas to create new pasture-lands. The number of ships and particularly of goats increased continuously, resulting in the overgrazing of the areas and hampering regeneration of the natural vegetation. In the mean time, the natural vegetation of many areas was cleared for cultivation.

The present vegetation of Crete is typical of the eastern Mediterranean, adopted to the dry climatic conditions of this region. The lower zone is characterised by maquis vegetation and particularly by evergreen shrub species such as Quercus sp, Arbulus unedo, Arburus andrachne, Phillyrea media, Pistacia lentiscus, Pistacia terebinthu. Apart from maquis, this zone is characterized by bushwood plants among which the most important species are Erica arborea, Erica verticillata, Genista acanthoclados, Poterium spinosum, Euphorbia acanthothamnos, Thymus capitatus, Anthylis hermaniae, Phlomis fruticosa and various species ofdstus.

Conifera are represented by the main species Pinus and Abies that comprise forests of economic value. Of similar importance but of smaller extent are the conifera species of Cupersus. Common pine species are Pinus peuce, Pinus leucodermis and Pinus halepensis. Other conifera such as Juniperus and Taxus are found but not forming individual plant societies. Annual plants commonly grown in Crete belong to the families of Graminae, Compositae, Leguminosae, Cruciferae, Caryophyllaceae, Labiatae, Umbelliferae and Liliaceae.

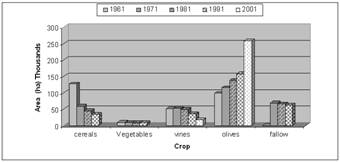

Olive and vine plantations are the main trees covering at present a great part of lowlands and the hilly areas, but also parts of the uplands. The great expansion of the olive groves occurred during the last 4 decades after eliminating the maquis and shrubby vegetation. Olives cover today 80 % of the soils in the footslopes of Psyloritis mountain. Vine plantations have greatly declined the last decades due to the destruction by phylloxera. New plantations, more resistance to phylloxera appear in the area the last decade (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Changes in agricultural land uses in Crete in the last decades (Agricultural Statistical Service)

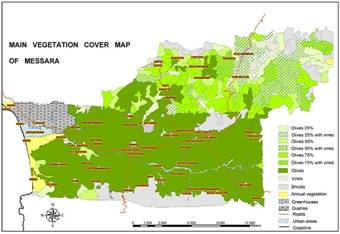

Figure 7: Map showing the main vegetation types of the Messara valley, Crete

The Messara valley is mainly covered with systematic olive groves or mixed olive groves with other agricultural crops or natural vegetation cover 80.8% of the research area (Figure 7). Vineyards are mainly found in the upper valley hilly areas. Spare trees or systematic olive groves in combination with natural vegetation or agricultural crops are mainly found in the upper hilly or mountainous area. Pastures including maquies and annuals cover 15.3 of the area and they are mainly located in the upper zone or they appear as patches in the lower zone surrounded by olive groves (Figure 8). Also greenhouses covering 3.8% are mainly located in the lower part of the valley where climatic conditions are more favourable for growing vegetables.

Figure 8: Typical landscapes and land uses of the Messara valley, Crete, covered mainly with olive groves and pastures in the upper hilly areas

Until 1920, the slopes of Asterousia mountains (southern of Messara Valley) were cultivated with cereals. Due to the evolution of mechanical cultivation, these areas have been abandoned, so that scarce phrygana comprise the natural vegetation of this area today. Vegetation is denser on the uplands of Asterousia Mts. and confine mainly to phrygana (Erica arborea, Erica verticillata, Genista acanthoclados, Poterium spinosum, Euphorbia acanthothamnos, Thymus capitatus, Anthylis hermaniae, Phlomis fruticosa) and various species of Cistus. Although the natural vegetation in the Asterousia area shows a capacity for succession to higher forms, this is not the case since the area is used for grazing during the winter months mainly by the inhabitants of Idi mountainous areas. Overgrazing of the regenerated young plants during this period ceases their growth degrading more and more the natural vegetation.