Groundwater, water transfers, and irrigation

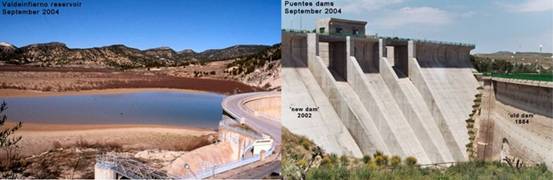

Due to the profound water deficit in large parts of the Guadalentín basin, irrigation has been applied since long times in order to sustain agricultural production. In Roman and Arabic times sophisticated irrigation schemes and water harvesting techniques were developed and widespread for decades. At the end of the nineteenth century two reservoirs were built (i.e. Valdeinfierno and Puentes) to store water for irrigation purposes. After an initial catastrophic collapse of the Puentes dam in 1802, both dams were rebuilt in 1897 and 1884 respectively. Although these reservoirs allowed the expansion of irrigated agriculture, this was only temporally, as both reservoirs were silted up rapidly. The Valdeinfierno reservoir is nowadays almost completely filled with sediments, and in the Puentes reservoir, that was also filled with sediments, a new and higher dam was finished in the year 2002 (see photograph 1).

Photograph 1: Images of the Valdeinfierno and Puentes reservoir in 2004 (Photos by J. de Vente).

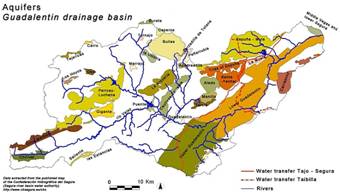

In the search for alternative water resources, the large-scale use of groundwater for irrigation started in 1950s, with the availability of better groundwater pumps and electricity in rural areas (Lopez-Bermudez et al., 2002). Figure 8 shows a map with the aquifers in the Guadalentín basin. Depth to groundwater in these aquifers ranges between 0 and over 200 meters.

Over time there has been a strong increase in the water-intensive crops. Therefore, in the upper Guadalentín the number of groundwater pumping stations increased from 25 to 234 between 1973 and 1996, resulting in a lowering of the water table by almost 10 meter per year (Tobarra-Ochoa and Martínez-Gallur, 1998; Romero Diaz et al., 2002). The total annual volume of extracted water increased from 24 hm3 in 1973 to 56 hm3 in 1990. In 1996 the extracted volume decreased again to 30 hm3 due to the lowering of the water table and the high price of water extraction from these greater depths. The irrigated agriculture used close to 83% of total water consumption in the Murcia region in 1999 (Rojo Serrano, 2004). The overexploitation leads not only to a lowering of the water table but also to salt intrusion and a severe salinization problem.

Figure 8: Overview of the main aquifers within the Guadalentín basin.

In order to deal with the overexploited locally available water resources, in 1979 the water transfer from the Tagus to the Segura River was opened. The water transfer was originally authorised to divert up to 600hm3 from the Tagus to the Segura River annually. Part of this water (25hm3) was intended for the Guadalentín basin (Tobarra-Ochoa and Martínez-Gallur, 1998). However, the droughts in the 1980s and 1990s made that less than half of the planned volume was actually transferred. Therefore, and in order to cope with the continuously increasing quest for water, various options for water transfers from either the Ebro or the Duero river basin are discussed at national level causing tense public and political debates (Lopez-Bermudez et al., 2002). Until now regional and national opposition towards more water diversions have prevented the creation of new canals. However, given the fact that irrigated agriculture at this moment is the only profitable form of agriculture without subsidies (Hein, 2007), there is a continuous political pressure to find more water.